Indie Rock: Teleglitch and Viscera Cleanup Detail

- Updated: 24th Jul, 2013

It’s mostly by accident that I’ve been playing two versions of the same game this week. I mean, I deliberately decided to play both of them because I retain a level of freedom allotted to me by the Human Rights Act and this is how I choose to exert it. I just didn’t realise what I was doing until I was flitting back and forth between game windows frantically shooting waves of enemies with what remains of my shotgun ammo, then elsewhere mopping up near-endless globs of stale, coagulated blood and throwing spent shell casings in a bin.

Teleglitch and Viscera Cleanup Detail are practically the same game, but at different points in time. Teleglitch is about a military facility being overtaken by hordes of monsters and you play as the single remaining human still attempting to move forward and escape.

Viscera Cleanup Detail is about that kind of narrative having already happened and you’re the guy left mopping and disposing of parts so that everyone can get back to work.

For as tonally different as these two games sound, and gosh they’re nothing alike even at all let’s not begin this pretender fun-house playtime, there’s a lot of overlap in their achievements. I’m going to talk about them separately!

Teleglitch

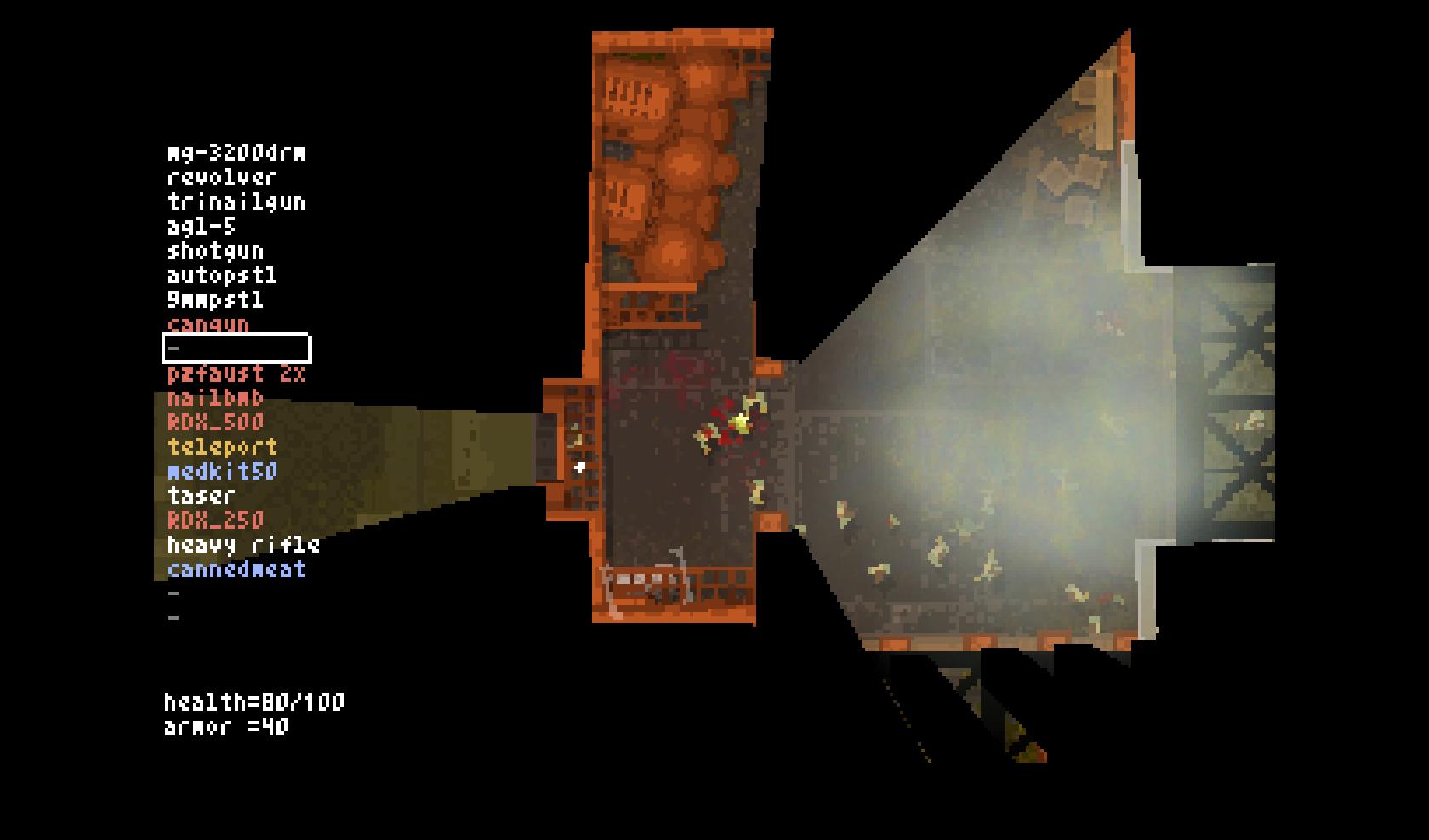

You’d probably call Teleglitch a roguelike if we were still a point in time where high profile games just started experimenting with some map randomisation. It’s interesting in that it leans into one of the genre’s biggest strengths, that you’re unaware of what to expect in the next room, underprepared for it and putting yourself at risk constantly, but each level is basically drawing from the same building-blocks and mostly contains the same kind of progression.

I am a purist about roguelikes. This shit is serious.

For a couple of levels Teleglitch’s deaths are permanent. You die and you’ll have to start over with zero progress and only your starting items of a pistol, some explosives and a can which you’ll find in the corner of the starting room.

Though you’ve initially got ammo to burn through, you really have to manage how much you’re using to deal with the hordes thrown at you in every room. It’s barely ever replenished and spending it all in an encounter means you’ll just have less of it later. That trade-off makes combat design both frantic and highly considered. You’ll run in circles around groups of enemies far outnumbering you, getting close enough to melee without letting them get close enough to hit you back. Even later, when you’re stacked with more weaponry, you’re still not able to get complacent about ammo conservation.

There’s a crafting system which forces you to make choices about your situation. Cans can be turned into armour, but it’ll take a lot of them to make it. You could instead craft them, along with explosives, into a one-use rocket hitting enemies from a distance, but that comes with the risk that you’ll miss and waste everything you’ve used. Some makeshift weapons are great for handling crowds, but backfire, causing damage to you too. I’ve barely gotten far at all into it, but gosh, play it if your one criticism of games with permadeath is that they aren’t difficult enough.

Viscera Cleanup Detail

My largest area of work experience outside of this “thinking of words to write about vid gam” is performing menial tasks for minimum wage, doing the same thing over and over until it’s done, then doing more of it again somewhere else. For about six months I worked at a supermarket stocking a grocery aisle. You’d make a list of everything on the shelves that needed replacing, grab a box of it one by one then keep doing that until more things had been bought, then repeat it.

Having to do that gives you an appreciation for the mundane. It was great exercise and almost therapeutic, spending a shift thinking about nothing other than all the things you could lift, take from one place and put somewhere else. VCD scratches that same itch for me, but instead of moving courgettes and bananas, it’s human ears and alien spleens.

You’re a lowly grunt dropped into a video game level after the danger has subsided. Your only task is to clean up all the blood, guts and spent ammunition. There’s a lot of gross mess in a video game level, it turns out.

Everything about this cleaning operation is stacked against you and will continue to get worse and worse until you clock off. You’re in the shit. No one above you cares that this job is tough and you still have to do it because you’re being paid to do it. You mop up blood and when your mop is too bloody you clean it off in a slosh bucket. You pick up body parts and throw them into a furnace or into endless supplies of bio-waste containers.

Minor problems emerge that are either entirely your fault or purely accidental, but don’t excuse you from having to clean up even more waste. You can knock over a slosh bucket that you’ve gradually filled full of blood and it’ll cover the floor and require you to clean up the same mess twice. You might drop an organ and it’ll bloody the floor up beneath it, or you could knock over a wastebin and have to pick it all up again.

There’s a great bit of emergent storytelling where one of your requests for more biohazard crates from a dumbwaiter-like machine will be met with an explosion of blood and unidentifiable body parts, as if someone was trapped inside the mechanism but now they’ve spurted out all over the floor.

And guess what. You’re cleaning that up.

There’s a strange sense of melodrama that Viscera Cleanup Detail offers in response to all the danger that came before it, as if the menace that tore apart the facility wasn’t really all that dangerous and world destroying if it was eventually sorted out and safety was returned. You read hastily drawn messages written in blood and detached from the cause your reaction is almost “Stop being such a baby about this, you didn’t have it bad. I’m the one with the mop, alright?”

Follow Us!