Prison Architect: My Mother and Me

- Updated: 10th Oct, 2013

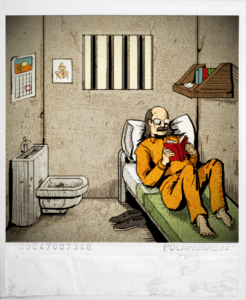

Prison Architect is built on a juxtaposition. Its big fonts and colourful, cartoony characters make it look like the kind of game you might let your kids play. But thematically, of course, it’s the dark side of adult, covering a range of prison-related topics from drug smuggling to the death sentence.

It’s the kind of game you wonder why anyone would play. From morbid curiosity, perhaps, or for a unique way to learn something. Certainly not for that good old-fashioned, escapist fun.

—

When my mother went to prison, I was at a loss. I wasn’t sad, and given that I’d already left home, my day-to-day life didn’t change at all. But on a higher level, I watched myself fail to react and I felt disjointed. I wasn’t sure what was supposed to happen to me, but surely it wasn’t nothing?

My teenage sister cried down the phone when she told me the news. Our little brother carried around a pillow from my mother’s bed. I came home from visiting them and just carried on as normal.

I told as many people as would listen, hoping that their reactions might give me a clue for how I was supposed to feel, but nobody knew what to say.

So when I received a timely press release about Introversion’s new game Prison Architect, it looked like some kind of sign. I’d read a lot of good stuff about other journalists having these emotional responses to video games, and I thought that maybe this could be mine.

At this early Alpha stage, Prison Architect is such a mess – so many features clearly thrown in because they sounded interesting, with no sense of balance – that it seems unlikely to provoke any emotion other than confusion. Nevertheless, and presumably because I was actively searching, I did make some connections. Simple cues made me feel sorry for my little virtual prisoners and by extension for my mother. Mostly, however, I looked at this OTT cartoon vision of life in a high-security facility for men and just thought about how she’s living in relative luxury.

She drew a picture of her room in a letter to my family, got a telling-off for it because apparently giving away the interior design of the prison can constitute an escape attempt, but got away with it somehow anyway. She has her own room with her own bed and her own key, like she’s staying in a university dorm. Only let’s face it, not many universities deck out student halls with flat-screen TVs.

The way she’d drawn her room, top-down like an architectural diagram, is the same way buildings are drawn on Prison Architect. It’s also the way she taught me to sketch out our home when I was a kid so that I could recreate it on The Sims, back before we started moving so often that I stopped bothering, back when we knew how to talk to each other without putting on an act or just having an all-out row.

Like with The Sims, playing Prison Architect consists of keeping a bunch of people alive and well. You design your prison around need fulfilment, so that each prisoner has somewhere to sleep, shower, and shit. They also have a few needs that Sims don’t have, like “Family”. At first, I thought they could only get that from visits, and I’d get annoyed because there’s no way to force visitors to come. Given that I haven’t visited my own mother yet, the irony was not lost on me. Even when I found out that fulfilling this need was as easy as buying phones so they could call home, it didn’t stop me from hiding in my family’s bathroom the next time my mother called when I was there.

Maybe I’m just cold, or maybe it’s reasonable to not know how to deal with a mother who went off to prison before we could deal with our long-soured relationship. But Prison Architect could have done more to encourage empathy. I mean, Gone Home got much closer to making me want to breach the silence between us, and that’s because of far less dramatic similarities.

Maybe I’m just cold, or maybe it’s reasonable to not know how to deal with a mother who went off to prison before we could deal with our long-soured relationship. But Prison Architect could have done more to encourage empathy. I mean, Gone Home got much closer to making me want to breach the silence between us, and that’s because of far less dramatic similarities.

—

You can hover over each prisoner to check on their needs, and also to look at biographical information. You can see what kind of family the prisoner has, and try to work out whether the creators are trying to play to stereotypes. Maybe it’s just me, but I saw a lot of convicts who’d had children at a young age. Maybe I was just thinking of my mother, who got pregnant with me when she was a teenager.

I pictured what her profile would look like. Family: an ex-husband, and children of various ages. Conviction: what a friend of a friend told me the other day is called “white-collar crime”. You know, the acceptable kind. The kind he could joke about during a group outing, which made me want to punch him because it doesn’t really make any difference. She’s in a low-security joint, sure, but she’s still tainted. She’s still always going to be a criminal, and me a criminal’s offspring.

Maybe Prison Architect understands this better than I first thought. You can split your prisoners into high and low risk, but the main point of the game seems to be that they’re all the same. Most simulation games treat people as nothing more than numbers, but it makes sense here because convicts are just numbers in real life too.

You can tell from her letters that this hurts my mother the most. She talks about the other prisoners as if they’re somehow beneath her, like she can’t bear the thought of being one of them. I could never imagine her as just one of a crowd. Maybe that’s one of the reasons I can’t bring myself to go and see her. Thank God she’s allowed to wear her own clothes, at least.

I thought of the little list of items my mother was allowed from home when the new update for the game came around, bringing with it a contraband system that included a way for prisoners could get visitors to smuggle stuff in, as well as a more logical way for prisoners to find contraband in the facility itself. You click on a button and the architectural diagram turns into a treasure map: drugs in the medical bay, potential weapons in the kitchen, booze in the warden’s office. My mother would go straight for the last one. Apparently she’s lost weight, and I’m willing to bet it’s a result of going from two bottles of wine a night to none. Given that when I tried to intervene before it just ended in tears, maybe this is the best way.

I thought of the little list of items my mother was allowed from home when the new update for the game came around, bringing with it a contraband system that included a way for prisoners could get visitors to smuggle stuff in, as well as a more logical way for prisoners to find contraband in the facility itself. You click on a button and the architectural diagram turns into a treasure map: drugs in the medical bay, potential weapons in the kitchen, booze in the warden’s office. My mother would go straight for the last one. Apparently she’s lost weight, and I’m willing to bet it’s a result of going from two bottles of wine a night to none. Given that when I tried to intervene before it just ended in tears, maybe this is the best way.

If I didn’t care about what people might think of me, I might even say that the reason I’m not sad that my mother is in prison is that it might be the best place for her, and Prison Architect has helped me to realise that. She isn’t just better off than my virtual prisoners in their high-security facility, she’s probably also better off than she was at home. Maybe she isn’t exactly happy, but maybe that just isn’t possible. Like my prisoners, who even with their needs all met would try to escape the moment they saw the chance, something will always be missing for my mother, not just in prison but in life. I’ve come to realise that I can’t make her happy, and I guess – for now, at least – I’ve just stopped trying.

At least in game development it’s often easy to know when something just isn’t ready, and you need to wait for a few months or years before everything finally comes together in a way that makes sense. When I was playing the Prison Architect Alpha, I was so determined to build the perfect prison that I restarted the game six times before I gave up. I still get emails about updates with fixes and new features, but I’m never tempted to dive back in. Somewhere down the line, the game will be finished. When that finally happens, I’ll go back, and see if I can get what I want out of it. Some things just need time.

Follow Us!