So Bad, They’re Good: What Awful Games Can Do for You

- Updated: 11th Jul, 2012

Grant Howitt plays a lot of bad games. It’s something approaching a hobby, really, and his collection of utter crap has almost overtaken his increasingly-small group of decent titles. He takes a look at what satisfaction these shoddy excuses for entertainment can provide.

I like bad games. That’s a bit of a sweeping generalisation, and I’m going to clear it up as we go along, but know this – I enjoy a really shoddy game almost as much as I do a proper, well-thought out and artfully developed one.

It can’t just be any bad game, of course. To truly succeed it needs to fulfil the following three categories, all of which are somehow massively elitist, I should warn you,

What Makes a Good Bad Game?

It has to be rare. I’m not necessarily talking about imported Japanese wonderfests, here – although by all means, I’ll give ’em a shot – but it shouldn’t be easily available. Part of the fun of picking up increasingly rare bad games is the delusion that I’m basically Johnny Depp in The Ninth Gate, only instead of wandering around Paris dealing occult books and screwing the Devil’s handmaiden, I’m wandering around Tooting pawing through the PS2 section in Console Exchange and screwing not very much in particular.

It has to be different. The PS2 was a goldmine for ridiculous titles that shouldn’t ever have been released, and even if they didn’t necessarily think things through and released an absolute bum-clinker of a game, the developers should be congratulated for doing something different.

Like a game where you play a jet plane and fire syringes at 80ft rampaging women – that’s a thing. That’s actually a real thing that was published by thinking, breathing human beings who put their trousers on the right way round and everything. Or a helicopter rescue game, which presumably takes place after more exciting games have finished and mops up the pieces. Or a game in which you must somehow race trains as though that’s actually a thing people can do.

Like a game where you play a jet plane and fire syringes at 80ft rampaging women – that’s a thing. That’s actually a real thing that was published by thinking, breathing human beings who put their trousers on the right way round and everything. Or a helicopter rescue game, which presumably takes place after more exciting games have finished and mops up the pieces. Or a game in which you must somehow race trains as though that’s actually a thing people can do.

I love it. I love the way that these games actually got made, and staggered blearily into my disk tray for me to marvel at. There’s no way it should have happened – at some point, someone should have just quietly taken the project round the back of the studio and shot it through the head – and that makes me happy.

Which is why bad games like Mission Impossible: Operation Surma, for example, don’t count. It’s almost pound-for-pound a Splinter Cell rip-off, and it’s done very little that’s even trying to be new. Aside from getting Ving Actual Rhames to do the voice of his character, but that’s not exactly challenging. He’s not busy. I bet he did it for a cup of tea and the bus fare home.

It has to have at least one redeeming feature. Anyone can write a truly awful game. Hell, I could write one, right now, with no prior knowledge of coding. It’d be called Alone in The Dark 2: Aloner in the Darker, and it just wouldn’t work. A black screen would display when you loaded it up and occasionally your computer would crash.

But it’s no fun to hate that game (I presume; I haven’t written it yet). There has to be something worth playing it for; whether it’s a ridiculous but engaging soundtrack, awful voice recording, or an entertaining smart-bomb effect that makes up for an otherwise unremarkable title. I’m not asking for flawed diamonds, but more a flaw with diamonds stuck to it. If you get me.

Take, for example, the tie-in game for Underworld: The Eternal War. Gameplay consists of walking your badly-drawn vampire (or werewolf) up some badly-drawn streets and fighting some badly-drawn werewolves (or vampires). It’s top-draw rubbish, and seeing as there’s only one joke – that this is a game so bad, it almost feels wrong to hate it – the fun wears off too quickly. Rather than being enjoyable dross, it’s just startlingly inept.

Take, for example, the tie-in game for Underworld: The Eternal War. Gameplay consists of walking your badly-drawn vampire (or werewolf) up some badly-drawn streets and fighting some badly-drawn werewolves (or vampires). It’s top-draw rubbish, and seeing as there’s only one joke – that this is a game so bad, it almost feels wrong to hate it – the fun wears off too quickly. Rather than being enjoyable dross, it’s just startlingly inept.

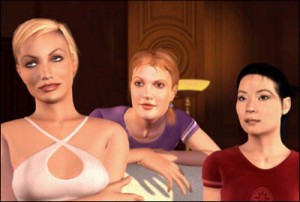

OR It has to be laughably, inexcusably poor. Take Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, for example.

So what can these games give us?

Information on how not to write games. Most of the games we’ll play these days are superb AAA titles which have been playtested and focus-grouped near into soft-edged oblivion. Even the ones that aren’t very inspiring tend to have exciting gameplay, or at the very least, gameplay that doesn’t make you want to rip your eyes out with a spoon.

If you play Halo, unless you think about it very hard, it’s impossible to tell how clever the level design is. That’s how clever it is. It’s like a good wig; you’ll never be able to tell if someone’s wearing a good wig, because… well, you get the idea.

Enter bad games. Suddenly, all the flaws start appearing. Levels where you can’t find the correct route. Enemies that are no fun to fight. Godawful checkpointing. Unsatisfying level ends. Shoddy weapon design. All the stuff we take for granted just isn’t here. If you want to make games yourself – or even just gain a greater understanding of how games are made, for a critical standpoint or to enjoy them on another level – then it’s important to see the mistakes as well as the failures.

A sense of smug self-satisfaction. Critical analysis, right, is hard. Take it from me. I write about games for legitimate outlets on occasion, and I can’t for the life of me work out why they keep me on, struggling as I do to crowbar even the smallest sliver of insight into my pieces. I can’t imagine that the other journos writing there are sat wide-eyed at their computer at one in the morning, endlessly paging back and forth through their notes trying to wring a semblance of meaning from where they’ve written “Tits! Explosions? YES.” in shaky, unsharpened pencil. I think I must be like a sort of mascot to them.

With films, games, books etc I have problems working out what’s actually going on, in a “talk about it knowledgeably at parties” sort of way. Which is why I like bad games. Bad games are easy to criticise. “This music’s rubbish,” you might say. “That character design is awful.” “Why would they write levels like this? It’s basically unplayable.” “God, who decided it was a good idea to put in a comedy sidekick?” And your friends nod and agree with you, and you can fit in for a while and feel like you’re even slightly worthwhile.

Something to do on a trip to town. If you want to buy good games, you buy ’em on the internet as soon as they come out. That’s what everyone does. Either that or you put down a pre-order in some high-street chain and, assuming that they’re not brought to the brink of collapse by lack of turnover, walk in early in the morning, hand over the cash, and walk out again without looking at anything else in the shop.

A passable GTA clone, marred only by the fact that the main character shouts “SPICY MOVE!” every fourteen seconds

The Three Minutes’ Hate. In 1984 – the book, not the year – George Orwell put in a daily activity for all citizens: they’d be led into a room and shown their sworn enemy on a vidscreen, and encouraged to scream and shout and get rid of all their anger in a safe, controlled environment so they could get on with the practical pursuits of spying on each other and, um, not much else.

I’m not encouraging games that reduce you to a shaking, frothing mess of rage – Mercenaries, for example, was a game with mission-ending events that managed to come as an infuriating surprise even when you were fully expecting them and I can never recommend that to anyone – but having a thing to deride – a clear, separate thing – is healthy.

One Comment